If you pick up an annual report these days, it is likely that you will encounter a slew of new information. For one, an increasing number of companies are beginning to report performance in safety-related objectives, primarily tied to incident rates and lost time. There’s also a greater amount of reporting around Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) initiatives, with organizations highlighting their performance against established UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). A recent article from the Harvard Business Review states that the number of companies filing corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports using the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) standards had increased a hundredfold in the past two decades. It’s worth noting that the article also questions the link between increased reporting and actual sustainable impact.

Under the broader umbrella of sustainability, there is an increasing push from organizations to adopt the circular imperative or become active in the circular economy. The European Union has even established a Circular Economy action plan for its member organizations. Large organizations such as Philips even have dedicated circular economy objectives as a part of their broader ESG approach.

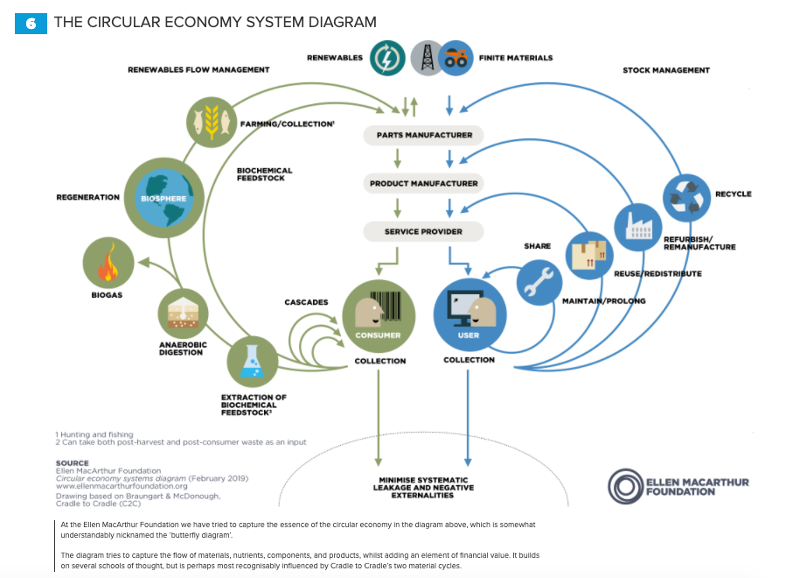

It’s worth taking a moment to understand the definition of the Circular Economy. As outlined by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a major player in the circular movement, the circular economy is a new way to design, make, and use things within planetary boundaries. It suggests that the three pillars at the foundation of this system are:

- Design out Waste and Pollution

- Keep Products and Materials in Use

- Regenerate Natural Systems

It argues that the move from a linear model of take>make>dispose to a circular one of make>use>return can have a significant impact on environmental as well as economic goals. For organizations that are serious about their circular ambitions, service plays a major role. This link between service performance and Circular outcomes becomes exceedingly clear when we unpack the 2nd foundational principle of ‘Keeping products and materials in use.’ At the end of the day, the mission of most service organizations is to maintain, to repair, and to enhance so that customers can tap into asset performance. Perhaps this is the right opportunity to align service-focused and Circular objectives.

Let’s dig deeper into the link between the two. As we look at the key areas outlined in the ‘Finite Materials’ section of the Ellen MacArthur foundation’s diagram of the Circular economy, there are interesting parallels with core service activities.

Maintenance and Extension of Useful Life

An argument can be made that manufacturers in certain industries are not focused on extending the life of their assets but are much more focused on driving faster replacements. This is particularly true in the areas of consumer electronics and consumer durable goods. As industrial organizations move towards the delivery of outcome-based services, there might not as much of an emphasis on extending useful life as a newer asset might be more efficient in delivering the necessary outcomes.

These are all valid arguments, but I still believe that these trends might lead to the replacement of an asset in one area, and a subsequent reuse of that asset in another area. For a majority of industrial organizations, there is an increasing push to invest in technology and processes that prevent breakdowns, improve performance, and extend overall asset life. This is often central to the mission of the service organization. More organizations are even offering additional services that target the efficient use and performance of assets to reduce the energy footprint, reduce maintenance costs, and increase output or overall equipment effectiveness (OEE).

Return and Reuse of Materials

There is a lot of attention paid to the forward logistics associated with equipment and service parts, but not as much to the reverse piece. Bringing parts and assets back into inventory or repair depots can have a significant impact on net new purchase and consumption of resources. Technician vans and forward stocking locations can provide an incredible amount of unused inventory that can be repurposed for other service and maintenance initiatives.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, many service organizations drove programs to reacquire as much excess inventory in their existing service networks to ward off potential supply chain disruptions. There is also a lot of used inventory and product that can be returned to repair and refurbishment centers and reinserted into the service ecosystem.

Repair/Refurbishment/Remanufacture of Parts and Assets

There tends to be a lot of focus on recycling when it comes to environmental initiatives, and this is an extremely important area, especially when tied to the third principle around regeneration. But there needs to be an equal amount of interest paid to Repair, Refurbishment, and Remanufacturing. In some ways, refurbishment and remanufacturing could be the ultimate form of recycling. According to a much-hailed United States International Trade Commission report (2012), the United States is the largest remanufacturer in the world (as of report writing) and the value of remanufactured goods in key industry sectors reached $43b. Yet remanufactured products only account for a small percentage of the total products sold.

The impact of this process on the economy and the environment is significant especially considering the repurposing of materials and resources (as opposed to their disposal in landfills) and the avoidance of acquiring or building new resources to produce equipment and goods. To be truly circular, an organization must consider the resources and tools to bring products and parts back (reverse logistics) into their facilities or those of their partners and then invest in the capabilities to either repair, refurbish, or remanufacture these products and parts for industrial use.

Role of Asset Data in the Circular Economy

These are some of the primary areas where the capabilities of the service organization are central to the circular economy. While these capabilities primarily align with the second foundational pillar of the circular economy, it’s also worth highlighting how service data captured throughout the entire asset lifecycle can impact the first principle of designing out waste.

When you pair design for serviceability with design for sustainability or design for reuse, the impact can be much more significant. If products are designed for easier repair, then this makes the extension of useful life a lot more economically viable. If they are designed for efficient assembly or disassembly or with modular components that can be updated and upgraded, then the impact on useful life is magnified. For circular to truly be successful, organizations must close the loop in their thinking of the product or asset lifecycle, all the way from design and engineering to service and remanufacture.

As circular initiatives gain attention and momentum, there will be increased recognition of the challenges in going circular. More so, there will be an increasing amount of scrutiny on the effectiveness and practicality of going circular. That said, organizations with intentions of going circular could start with looking at their own approach to asset lifecycle management and by shoring up vital service processes and ecosystems.

Share this: