When advising field service leaders eager to try out new technology, John Rygg doesn’t mince words: “You can’t be afraid to fail.”

Rygg is a technology strategist for Kiewit Corporation, one of the world’s largest construction firms working with large-scale infrastructure projects such as dams, bridges, and airports. In this role, Rygg scouts out and tests the latest emerging technologies that could help Kiewit’s engineers and designers to do their jobs better.

“Sometimes a failure is just as good as a success,” he says. “You understand how things might work better next time, and you reset your expectations.” That embrace of failure is the most important technology adoption lesson that Rygg has learned. It is a mindset familiar to the technologists who build the next-gen gadgets that Rygg tests.

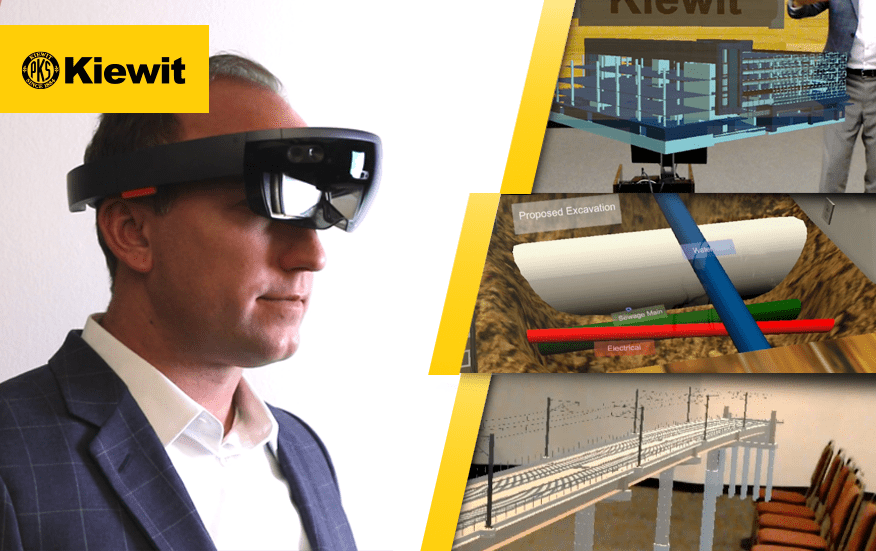

When Rygg finds a promising new technology — such as Microsoft’s HoloLens augmented reality (AR) headset, which Kiewit engineers use to visualize and interact with 3D construction project models — he’ll bring it to job sites to get feedback from the Kiewit teams that would actually use the tech. Rygg asserts that this is the second important step when adopting new technology. Don’t be afraid to fail. But don’t guarantee failure by ignoring users. Often, Rygg says, those users provide creative inspiration for how a new technology could be used, ideas that Rygg couldn’t dream up alone.

Don’t be afraid to fail. But don’t guarantee failure by ignoring users.

“Traditional IT people ask, ‘What’s your problem?’ and then find technology to fix it,” Rygg says. “I work the opposite way. I find technology that might be useful and I give it to people in the field and ask, ‘Could you use this to solve your problem?’” This approach provides him a broader view of how the tech might be used, and whether it’s workable at all.

Image courtesy of Kiewit.

Bringing tech to users is a key step, Rygg says. While users in the field may have inklings about shortcomings in the tech they use, they may not know what could improve their lives – nor might they know enough about new tech that’s out there to tell Rygg, “I need augmented reality.”

“They may have never worn a headset like a HoloLens,” says Rygg. “They don’t have a point of reference for it. That’s why we need to place it in their hands, so they can tell us, ‘This is great, but we’d use it this way.’”

That process is how Rygg learns which emerging tech tools — from drones to autonomous vehicles — will be eagerly adopted, and which ones are better left on the shelf. Take the HoloLens, 12 of which Kiewit has deployed for large construction projects. They don’t work well in bright daylight, so for engineers in the field, Rygg is more likely to recommend AR apps that work on tablets and mobile phones.

Watching and Learning from Experts in the Field

“Every time I go out to a project site, I learn something new, which means I can make better-educated guesses about what field teams need,” Rygg says. “They’re the experts.”

Even something as simple as a software app can be an adoption win or fail, depending on what project leaders learn about field users. For example, deskbound IT teams might lean toward creating apps with loads of information, assuming that field engineers might welcome more data. The reality, Rygg says, is that field workers need apps that are easy to use and have just a few buttons to click — and are not overloaded with features they don’t need for simple tasks.

“In construction, people are wearing protective clothing, gloves, and safety glasses, and they’re often in noisy, bright environments,” Rygg says.

Kiewit’s technology strategy team, based in Omaha, routinely sends user experience (UX) experts into the field alongside software developers to learn how people in the field do their jobs. The team spends about one-third of its time in the field at project sites. In field environments, the KISS principle (“keep it simple, stupid”) is the best methodology, according to Rygg.

Traditional IT people ask, ‘What’s your problem?’ and then find technology to fix it. I work the opposite way. I find technology that might be useful and I give it to people in the field and ask, ‘Could you use this to solve your problem?’ — John Rygg, Kiewit Corporation

“Maybe the project is in an area with poor bandwidth, or maybe voice commands won’t work if it’s noisy. Even if a piece of complex technology might be technically better for the job, it may not be durable in the field.”

In fact, phones and tablets, which are familiar devices for most field technicians, can be the most effective launching pads for new tools.

“There are a lot more AR applications being built around phones and tablets, and phones are getting more powerful all the time,” Rygg says. “It’s easy to get wrapped up in technology for tech’s sake. But phones and tablets are in the field already, so we should use them.”

It’s All About the Data

In addition to monitoring AR technology, Rygg is keeping an eye on Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, which he thinks are moving past the hype curve and show potential for field use. But he’s moving slowly — a strategy he favors. It’s not a bad idea to check out technology that’s getting hyped. On the other hand, organizations shouldn’t invest in hot new tech until they’ve gone through Rygg’s steps for testing tech with real-life users.

“IoT devices are like drones — it’s not the device so much as whether you can do something with the data you gather,” says Rygg. “With IoT, I’m still looking for a useful app on the back end that takes the data and gives you something actionable.”

Rygg regularly makes the rounds at big tech events like the Consumer Electronics Show to investigate technology that may just be starting to make inroads into enterprises — or are starting to turn up in consumers’ hands. In fact, consumer tech trends give Rygg hints about what may be required equipment for field teams years down the road. “A lot of that technology ends up in the enterprise, like drones,” he says. “It’s a good idea to view consumer technology trends as your roadmap.”

Share this: