From his home base in Halifax on Canada’s Atlantic coast, Darrell Groom can expect, at a moment’s notice, to be sent on a service call anywhere on Earth. It comes with the territory for a project manager whose clients include navies and scientific organizations around the world.

Darrell Groom, Project Manager, AML.

Groom’s company, AML Oceanographic, employs about 40 people on both coasts of North America and in Scotland to design, manufacture and service a variety of hydrographic surveying systems that navies, government agencies and private companies use to collect a variety of oceanographic data, including water salinity, temperature, and the topography of the seafloor.

Groom, however, is focused on the AML’s Moving Vessel Profiler, or MVP, product. He leads a team of six engineers and services technicians who keep the company’s MVPs operating wherever in the world the systems might be deployed.

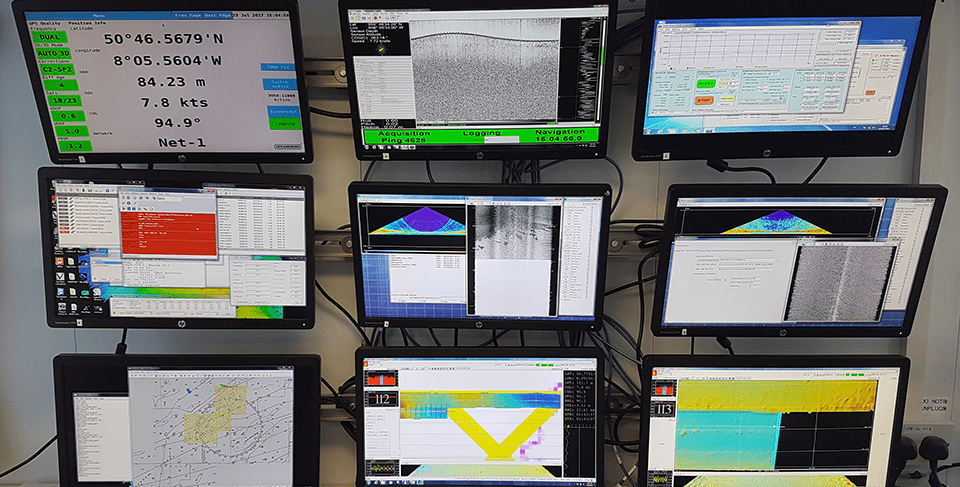

The MVPs consist of hardware, high-tech electronics and software, though each model varies in size and complexity depending on customer needs. Components include a mechanical crane and computer-controlled winch to lower and raise the device into the ocean, and a torpedo-shaped device that’s towed behind the ship. Roughly the length of a human arm, the tow body is studded with sensors that beam readings to a computer onboard the customer’s ship.

So far, about 130 MVP systems have been sold around the world. Clients include navies (to map the sea seafloor and spot submarine hideouts), oil and gas companies (to survey potential undersea drilling sites) and scientific agencies (to conduct oceanic research or to update coastal undersea terrain that changes constantly because of storms and underwater currents). These organizations rely on the MVP to improve data quality and to contain mission costs. But the complex devices require regular maintenance, which often falls to customers. And that can create problems.

The MVP allows research institutes, navies and businesses to collect a variety of oceanographic data to profile the water column.

Once a survey mission is complete, the crew responsible for MVP’s maintenance might rotate off the vessel, leaving the system unused as the ship and its crew pursue a different mission.

“Similar to a car, our equipment may not work when you try to fire it up, and sometimes a system will experience problems only a few days before a survey,” says Groom, who has a background in electrical engineering.

That, Groom says, is when his field service team gets called to fix the problem.

Making On-the-Go Research Possible

The MVP is so prized — and Groom is so very much in demand as a troubleshooting service tech — because the system can significantly reduce the cost of survey missions.

Using conventional survey technologies, a research vessel must make frequent stops to collect profiles of the water column by dropping and retrieving sensors and other instruments. This start-and-stop method is expensive and time-consuming — ocean survey missions costs can spiral to hundreds of thousands of dollars per day — and also increases the risk of damaging equipment as crews deploy the equipment into the water.

The MVP solves this problem by allowing crews to collect data simultaneously from the vessel and the tow body while the ship is on the move. The computerized winch uses locational data from both the tow body and the vessel itself to automatically adjust the depth of the tow body to avoid the seafloor. This means the vessel can follow its survey pattern without ever needing to stop and retrieve the tow body and its array of sensors.

See also: Deep Dive Maintenance: Field Service in ‘The Abyss’

Since costs from even brief outages or downtime add up quickly, Groom says customers are willing to fly his team in to fix problems they can’t fix themselves. AML offers service contracts, or customers can opt to pay on an as-needed basis. Scheduled maintenance is sporadic, he says, because the systems are designed to be highly reliable.

Worldwide Dispatch

Groom recalls a recent call from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the agency responsible for charting U.S. coastal waters, which had a problem downloading data from the MVP. “They needed someone to go up to Alaska right away.”

Similar to a car, our equipment may not work when you try to fire it up, and sometimes a system will experience problems only a few days before a survey. — Darrell Groom, AML Oceanographic

Groom spent one day planning the trip and caught several flights for the 14-hour journey from Halifax to Ketchikan at the southern tip of Alaska’s panhandle. But his trip wasn’t finished yet.

“When I arrived at the harbor they were waiting for me with a Zodiac inflatable boat to take me out to the survey vessel,” Groom says. “It turned out that the tow body was slightly damaged, so I improvised and MacGyvered a solution that allowed them to collect data and continue the survey.”

Groom’s service calls, as well as trips to install and set up MVP systems have taken him on some memorable trips, including cruises from the Azores and between American naval bases in Okinawa, Japan, and Saipan.

“When I arrived in Saipan, I realized I was booked into a five-star vacation resort, so I was forced to stay there for a few days until my flight home to Halifax,” Groom jokes.

MVP at work in the Arctic. Photo: AML Oceanographic

One of his most memorable service trips was to Ireland, where thieves stole most of his tools from the back of a rental van. While transporting the MVP to Dublin, Groom and the client spent the night at a hotel close to the airport. There were concerns in the area about theft, so Groom backed the van against a chain-link fence.

“The thieves simply cut open the chain link fence, pried the doors open, and stole all of my tools,” says Groom.

But the story has a happy evening: He was able to improvise with borrowed gear, and Dublin police eventually recovered the stolen tools.

For the most part, service calls out at sea are for unusual problems that stem from neglect or preventative to keep the reliable MVP systems in shipshape.

AML provides training and documentation to its clients on how to use and maintain the system, but Groom says that institutional knowledge isn’t always transferred between crews as they rotate through survey vessels.

“As people move through the ranks they take a lot of valuable knowledge about operating the MVP with them,” says Groom.

He recommends that customers deputize at least one person on each vessel to own upkeep and maintenance for the system.

“It can be difficult for customers to perform daily, weekly and monthly maintenance,” he says. “Someone needs to have ownership of the MVP, but for the most part this doesn’t happen. They just want it to work when they do a survey.”

As a result, Groom is certain he’ll keep getting phone calls to depart at the drop of a hat to almost any place in the world to service the MVP.

Featured image courtesy of Pexels. All other images courtsey of AML Oceanographics.

Share this: