At the General Electric Aviation facility in Cincinnati, Ohio, factory technicians are accustomed to working from paper instructions when performing engine maintenance. Recently, though, they’ve traded in their paper manuals for digital instructions via Google Glass.

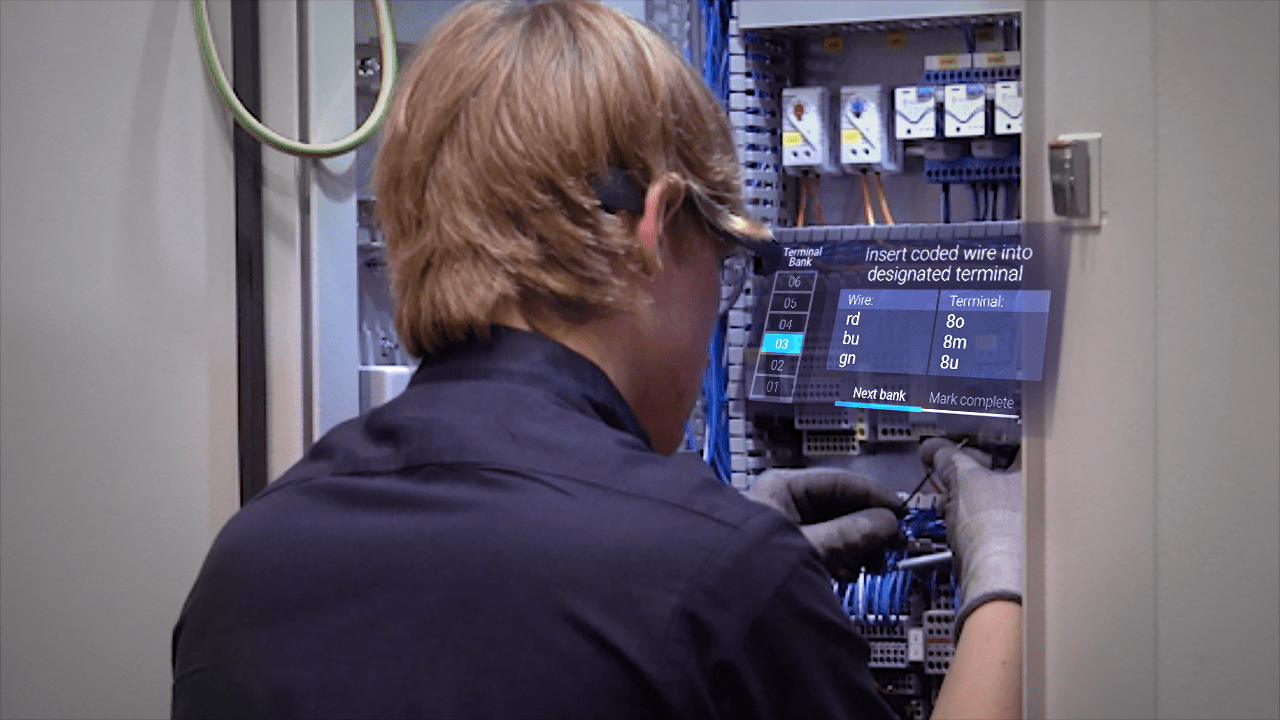

What was a consumer flop for the search engine giant in 2013 is roaring back in 2017, rebranded as Glass Enterprise Edition, a version designed exclusively for factory workers, warehouse employees and field technicians.

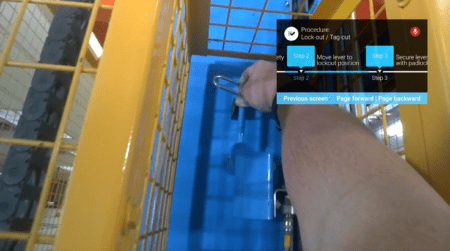

Technicians at GE Aviation receive instructions directly in their lines of sight on headworn Glass EE devices, accessing real-time guidance on the tasks they’re performing, instead of relying on books or manuals. During a summer pilot program, GE found that using Glass EE increased productivity by as much as 12 percent for both experienced and new workers.

A technician gets an AR assist from the latest version of Glass. Photo: Upskill

“We’re helping connect workers to the information they need to do their jobs effectively without having to take their hands off the work they’re performing,” says Aaron Tate, vice president of client success at Upskill, a Washington, D.C.-based company that develops the software that big companies use to deploy augmented reality devices like Glass for hands-on work.

Beyond increasing productivity on the factory floor, devices like Glass have huge potential to transform service work at remote sites away from expert guidance. Not only can service techs use the headworn displays to digitally access the most up-to-date technical manuals—the technology also lets them livestream what they’re viewing via the device’s camera, giving a bird’s-eye view to any experts whose help they might need to complete a project.

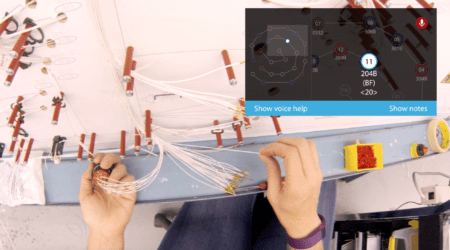

Upskill’s software, called Skylight, lets companies map their existing processes into headworn displays so that workers can retrieve critical information in real time. Since 2014, Upskill has been piloting this software across a number of headworn devices inside GE and Boeing—and not only Glass, but also Vuzix’s M300 Smart Glasses and Microsoft’s HoloLens. It was Upskill that provided GE with the software to complete its summer Glass pilot project at its Aviation facility. (GE Ventures is an investor in Upskill.)

A Boeing technician installs wiring with Google Glass Enterprise. Photo: Upskill

In the field, several major companies are already pairing Skylight software with wearable displays. The Coca-Cola Bottling Company in the United States uses Skylight whenever field workers need to perform maintenance on factory equipment, equipment that is manufactured in Europe, notes Tate.

“The techs who would maintain or fix those pieces of equipment [are located] in Europe. So, if the equipment would go down, people from Europe would have to come, incurring a stoppage in production,” Tate says. “That’s one scenario we’re seeing where having a set of Glasses at each factory is helping to increase productivity and reduce the amount of trips of experts to [bottling] sites.”

Field service agencies for Boeing are also using Skylight software with wearable displays. Boeing’s latest service reports and manuals are connected, via the software, to technicians’ displays, meaning that even third-party field service workers can access updated Boeing technical data for any maintenance.

Google Glass Enterprise. Photo: Google

At the moment, mostly larger companies are employing the wearable devices and software, companies that have the money to invest in cutting-edge maintenance technology. But Tate says the benefits that company workers are reaping can be a boon to smaller companies as well.

“Using the Glasses, a worker can call back for support and share what they’re seeing in real-time audio and video, rather than waiting for someone else to come out and travel to them,” Tate says. “It’s a huge cost avoidance.”

As for training field service workers to use the new technology, Tate says that’s the easiest part of the process. Typically, it takes workers about half a day to learn the software and hardware, and then a couple of months of using the technology in the field to increase their proficiency. In many cases, new field technicians prefer the digital tools to paper manuals.

“We’re seeing a field workforce coming in that’s already experienced the technology,” says Tate. “It attracts more people into field service.”

Hi,

I will like to understand more and contact Upskill for google glass. We do have complex equipments and will like to explore it to facilitate our field engineers. Can you pl provide me their contacts ?