Late winter seems like an unlikely time for people to be bustling around an amusement park on the Brooklyn shoreline. And yet, on a morning last month, there wasn’t an idle body to be found. Men are pulling out cars from a kiddie ride due for maintenance and a quick clean, while others remove signs and lighting from winter storage.

For park mechanic and owner Deno Vourderis Jr. (known as D.J. to most) and his family, this is the final push until opening day on Sunday, April 9 — and it’s all hands on deck.

Vourderis’ grandfather, Deno Sr., once worked for the original owners of the park as a Ferris wheel mechanic. He eventually purchased the park from the son of the original owner-operator in the 1980s, after the park had fallen on hard times. Since then the park has been handed down to Vourderis’ father, Steven, and his uncle.

Since Vourderis’ childhood, keeping the park running has been a family affair. Today, several relatives work there, part of the roughly 10 full-time employees who work at the park during the off-season and the 80 to 90 who work during the summer.

Vourderis remembers working at the park alongside his brothers, cousins, uncles, and father as early as the first grade.

“Whenever my father had to drive me to school, I ended up here instead.” He says at that age he was doing less of the mechanical work and more of the painting.

“Once I finished college and could be here in the winter time, I started getting involved more and more with the maintenance, fabrication and all of the technical [tasks].”

An Unlikely Path to Amusement Park Tech

Vourderis is part of the latest generation to inherit the park, though he’s an atypical park mechanic and owner. For starters, engineering was never part of his formal education. He attended high school in Manhattan at the legendary LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing arts. The school boasts Liza Minelli, Al Pacino, Jennifer Aniston, and Nicki Minaj as graduates. After high school, Vourderis studied political science and acting at Hofstra University. Never did his academic studies lead him into trade or engineering courses.

All the math and science in the world wouldn’t help me build things that I do without LaGuardia.

Despite his liberal arts background, Vourderis has the skills of a highly adept engineer and mechanic and has made key improvements to most — if not all — of the park’s 21 rides. He taught himself how to build and integrate new solutions by tinkering and researching on his own. But Vourderis points to his experiences at LaGuardia High School as his inspiration.

“What made me who I am, was the passion that I learned from this amazing place. All the math and science in the world wouldn’t help me build things that I do without LaGuardia.”

Vourderis also comes by it naturally and credits his father for his innovative problem-solving gene.

“That’s more my father. I do it more with ones and zeroes, but he does it more with steel and hammer,” he says about bringing digital savvy to a century-old park. “He does all of the mechanical part. He has the mind for that. I have the mind for that, too, but I got it from him.”

Old-School Fun, New-School Tools

Along with uploading YouTube videos of the jury-rigged fixes he’s created at the park, Vourderis is bringing his family’s park “kicking and screaming,” as he says, into the 21st century.

Vourderis has also been the driving force behind some of the latest updates to the park, including a 3D printer, solar powered lights, and a virtuality reality ride this summer that will take park-goers on a zombie hunting excursion.

Despite the vintage, boardwalk feel of the park, there are hints everywhere of Vourderis as the consummate modern Renaissance man. In the park’s main workshop, he has transformed a workbench into a coffee station that rivals what you’d see at a boutique coffee shop in Manhattan.

“I have a ritual,” Vourderis says. “I start with only the purest water, then I have an induction cooktop where I boil my water. The station is complete with a scale and grinder for beans. “I always grind the beans fresh before I make them.”

“We had to rebuild a lot,” he says. “That’s when I learned a lot about electronics — I had to.”

Vourderis — along with his brothers, cousins, uncle, and father — is still working to reinstall certain parts of the park, such as the solar panels. “It’s a long job that we just haven’t had a chance to do yet,” he says. Getting the solar power light system working again also involves replacing each individual LED bulb he installed.

But he has a new toy, a 3D printer, he expects will help speed up the process.

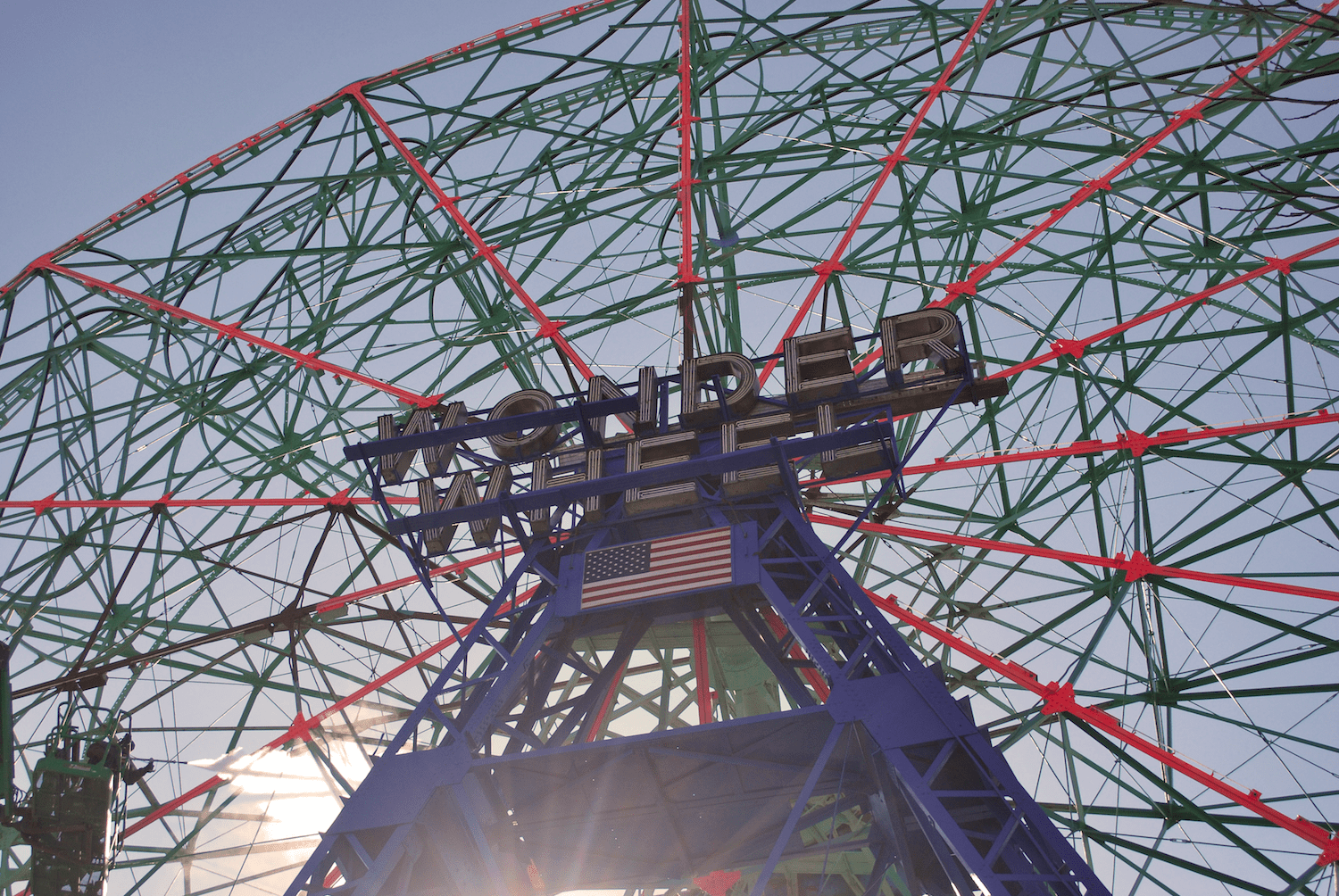

In a corridor of the park’s workshop, kiddie cars designed to look like open-air SUVs are lined up, each fitted with 3D-printed brackets to hold new LED light bulbs. Just steps away, a welder named Tom and his son thread and bend new turnbuckles for the Wonder Wheel using techniques and tools known to any blacksmith.

Tom has worked with the Vourderis family for 20 years and his own father worked as a welder for the park. Tom is considered family to the Vourderises, as are the other workers who keep things running smoothly, many of whom have worked there for at least 15 years.

Constant Tinkering — and Improv

The wheel itself is an intersection of technological innovation and tried-and-true, old-school engineering.

“This is mine. I made this,” says Vourderis, unveiling a modified control panel for the Ferris wheel with buttons that change the speed and pay homage to his “Star Trek” fandom. The panel stands beside the original crank-like switch from the 1920s that still works as a backup system.

“The future is tough because what we’re known for is being classic Coney Island. So we don’t want to lose that,” Vourderis explains the balancing act of remaining a place for nostalgia while remaining relevant. “You gotta walk the line between the two.”

Across the park, Vourderis approaches two workers manually turning the carousel as another stands on a ladder reattaching lighting and facades as the ride slowly rotates.

“You want my wireless remote?” Vourderis asks. “Come on, I have a wireless remote for that!”

Read more about Deno Vourderis’s mix of old-school and new-school tools in the April issue of Field Service, a quarterly print magazine published by ServiceMax and Field Service Digital.

Share this: