From faulty toilets to full-blown electrical system outages, service doesn’t get more extreme than NASA’s work in space. And when something goes wrong, astronauts double as service techs.

Many extraordinary things can go wrong for astronauts on the International Space Station, but one of their biggest concerns will be familiar to even the average homeowner: broken toilets.

There are two zero-gravity commodes on the ISS, and both have systems so complex that they make your American Standard look like a hole in the ground (which explains their $19 million price tag.) When they’re working, the ISS toilets are technological masterpieces, containing waste in weightlessness and transforming urine into potable water.

But when something goes wrong, somebody’s got to be the space plumber. That’s when the NASA’s Operations Support Office comes in. Its flight controllers are responsible for showing astro-repair people how to make necessary fixes on the ISS by uploading instructions and photos from mission control.

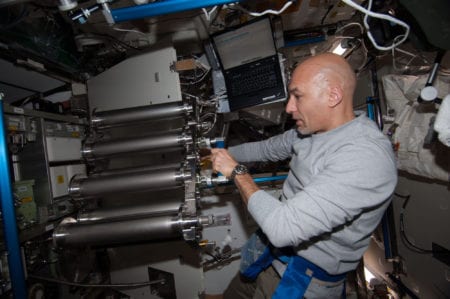

European Space Agency astronaut Luca Parmitano, Expedition 36 flight engineer, removes and replaces the particulate filter for the Water Pump Assembly 2 (WPA2) in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station. Photo: NASA

“There’s no one person who handles the difficult maintenance. Everybody’s trained to be at the same level of competence,” says Nikki Bullock, flight controller with Operations Support. “But toilet repairs are one of the toughest jobs for anyone.”

Astral Problems, Earthly Tools

Bullock’s department is in charge of “interior” maintenance on space vehicles, and while the orbiting systems may be exotic, much of the work is similar to what any technician would find on earth: repairing electrical circuits, replacing filters, and finding leaks, among other problems.

NASA astronaut Karen Nyberg, Expedition 37 flight engineer, works on the Multi-User Droplet Combustion Apparatus (MDCA) in the International Space Station’s Harmony node. Photo: NASA

The tools that astronauts use are those you’d find in the average toolbox: socket wrenches, screwdriver sets and locking pliers. In addition to everyday tools, the ISS is stocked with a number of repair kits for soldering, fixing electrical wiring and cables, and patching leaky pipes.

Experience has shown where problems are likely to crop up, so astronauts train in how to make a wide variety of repairs in the months before launch.

“Some astronauts are naturally handy,” says Bullock. “They’ve got that ability to look at something and figure out how it works. Others work better with some detailed instruction on how to make a system repair.”

In addition to learning about the systems on the ISS, astronauts spend time with aircraft technicians on the job to get a feel for the tools and experience working in tight, hard-to-reach spaces.

Tricky Repairs in Zero Gravity

One thing astronauts can’t master until they’re in orbit is the challenge of making repairs in zero gravity.

Jobs that can be simple while on earth, such as replacing a filter, can take hours when moving and safely stowing equipment to access a panel deep in the hull of the ISS. Small parts can easily get lost in weightlessness. The washer on a screw may drop harmlessly to the ground on earth, but it can drift into machinery when floating in the space station. And while tools like magnetized screwdriver bits are handy to keep small pieces in place down here, they’re not practical up in space.

Experience has shown where problems are likely to crop up, so astronauts train in how to make a wide variety of repairs in the months before launch.

“Because of all the electronics, we don’t want magnets on the ISS in order to protect the equipment,” says Bullock. “We’ll often use tape to contain small items, and in the instructions we’ll point out where all of the ‘non-captive’ parts will be so they’ll be ready for them.”

Improvising Repairs on the Fly

The flight control staff has anticipated most repairs, but there have been times when some critical work has required creative thinking, Bullock says.

Astronauts Peggy Whitson and Jack Fischer work on station systems inside Japan’s Kibo laboratory module. Photo: NASA

During one mission, a bolt receptacle on the exterior of the station needed to be cleaned out before the bolt could be put back. The problem: No one knew just how to do that in space. The entire flight control staff was enlisted to come up with a solution, and they devised a novel solution—attach a toothbrush to a wrench to scrape off the debris.

“It’s those moments that you really love in this job, where you find ways to keep the mission on track,” Bullock says.

Currently, NASA’s Operations Support is concentrating on teaching astronauts how to make more in-depth repairs. For example, on the exterior of the ISS are four solar-powered power switching boxes, called main bus switching units, that power hardware on the station. When one has failed in the past, NASA has had to replace the entire unit, taking up precious space on cargo crafts sent to replenish station supplies. The hope is for astronauts to repair these units in space. NASA has already notched a success in making this goal a reality.

“The robotic arm was used to remove one of the units and it was brought inside through the air lock,” Bullock says. “The crew opened it up and made a repair, then the unit was reinstalled outside. It was a big achievement, and it’s something we hope to do more of in the future.”

Share this: